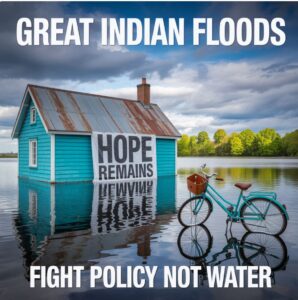

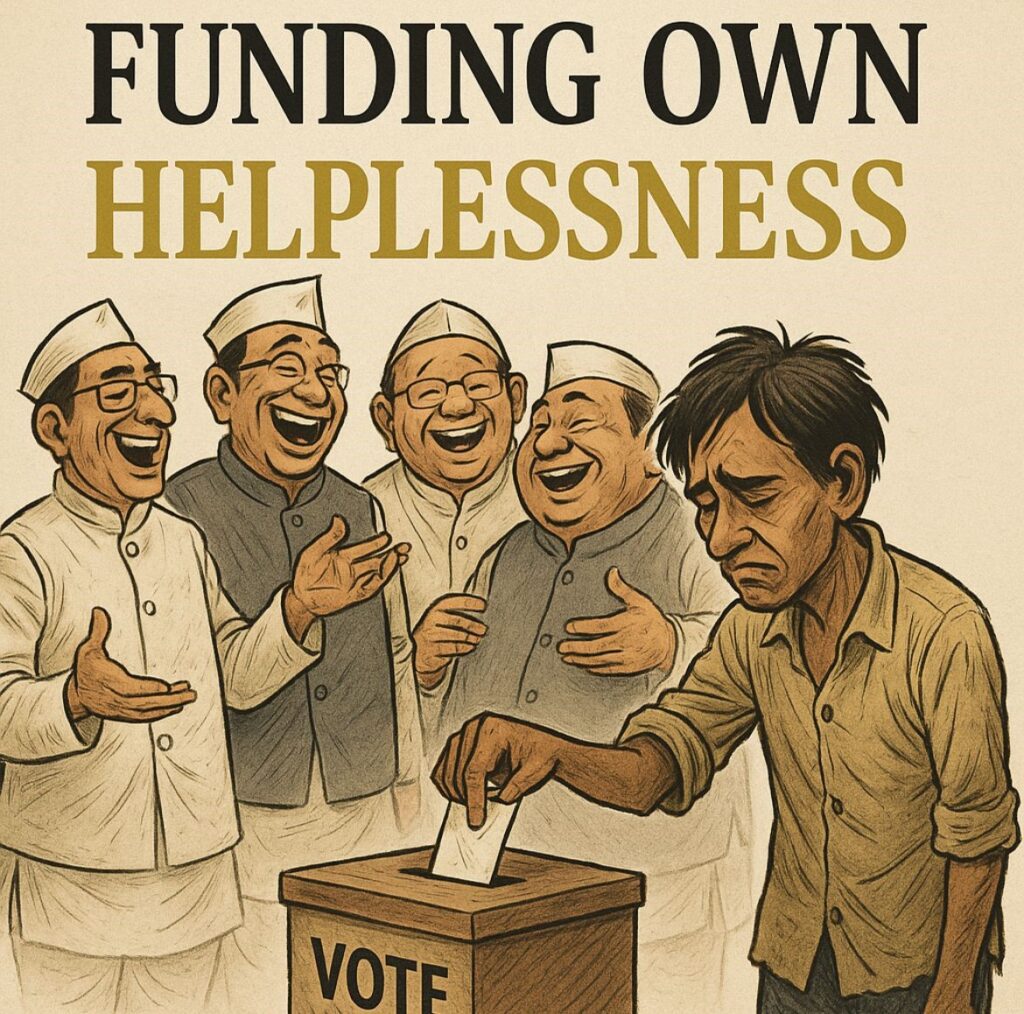

How Indians Finance Their Own Helplessness – Largest Democracy, Powerless Voters

India’s democratic paradox: citizens fund the state yet remain functionally disenfranchised between elections

The arithmetic of Indian democracy reveals a stark paradox. In FY 2023-24, the Union government’s revised estimates show total receipts of approximately ₹36.24 lakh crore: ₹23.24 lakh crore from taxes, ₹3.00 lakh crore from non-tax revenue, and ₹10.00 lakh crore in capital receipts, predominantly borrowings that future taxpayers must service. Strip away the accounting complexity and the reality is unambiguous: Indian citizens finance the very machinery that renders them inconsequential once the ballot is cast.

The Citizen as Involuntary Investor

Consider the revenue composition more closely. Direct taxes contributed ₹17.47 lakh crore, with individual taxpayers, largely salaried employees and professionals, accounting for ₹9.22 lakh crore. Corporate taxes added ₹8.25 lakh crore, whilst indirect taxes through GST, customs, and excise duties extracted a further ₹12.4 lakh crore from consumers and businesses. Non-tax revenue of ₹3.00 lakh crore flowed from public sector dividends, resource monetisation, and fees, ultimately derived from economic activity generated by citizens and enterprises.

The borrowings of ₹9.30 lakh crore represent perhaps the starkest illustration of democratic dysfunction: future taxes signed into existence without the consent of those who will pay them. No institutional investor would accept such terms—continuous capital provision with no governance rights, no performance covenants, and no exit mechanism for five years.

The Fiction of Representation as Recourse

The standard defence of this arrangement holds that citizens possess adequate recourse through their elected representatives, grievance mechanisms, and the courts. This argument deserves serious examination against lived experience. Representation dilution occurs immediately upon election. Power centralises within party hierarchies, coalition mathematics, and executive discretion. Constituency mandates regularly succumb to political arithmetic, leaving voters’ intentions subordinated to considerations entirely beyond their influence.

Democratic lock-in compounds the problem. Whilst citizens provide revenue continuously, their consent is captured episodically. No structured mechanism exists for mid-term performance review or mandate enforcement, even when core electoral promises collapse entirely.

Prohibitive transaction costs render theoretical rights practically meaningless. RTI applications, petitions, legal appeals, and departmental follow-up demand time, literacy, financial resources, and procedural stamina—luxuries the ordinary citizen rarely possesses. Systemic opacity ensures that spending data, procurement records, and subsidy distribution remain fragmented across departments. Without accessible transparency, intelligent challenge becomes impossible. Information asymmetry functions as pre-emptive disempowerment.

Institutional lag further undermines citizen recourse. Courts face massive backlogs, grievance systems lack enforcement mechanisms, and ombudsman structures operate without meaningful sanctions. A right that materialises years after harm is suffered serves purely decorative purposes. The constitutional ideal that “government is your recourse” thus collapses under operational scrutiny. The machinery exists, but the system withholds access to meaningful remedy.

The Hostage Elector Phenomenon

This creates what might be termed the “hostage elector problem”—citizens find themselves bound to a forced, illiquid exposure resembling an unsecured perpetual bond callable only by the issuer. They contribute capital daily through taxes and fees but can rebalance their position only every five years by swapping one macro-bet (Party A) for another (Party B), regardless of which specific ministry, department, or contractor has failed them.

The lifecycle of democratic powerlessness follows a predictable pattern: citizens cast ballots granting full fiscal mandates, then spend five years paying taxes whilst encountering broken promises and service failures, with only slow, costly grievance channels available until memory fades and the cycle begins anew.

Borrowed Authority, Inherited Debt

The Union’s ₹9.30 lakh crore borrowing programme represents perhaps the clearest violation of democratic principle. This debt constitutes an IOU drawn against the future earnings of today’s children, authorised without their pre-approval and carrying no mechanisms for exposure limits or public consent. Interest payments, rollover risks, and inflation consequences will burden citizens who never agreed to the leverage and rarely see debt sustainability discussed in accessible terms.

A Charter of Rights for Citizen-Financier

Reform requires recognising that voters, as the state’s principal financiers, deserve rights proportional to their fiscal contribution. A practical framework might include:

- Real-time financial transparency through unified public dashboards showing allocation versus actual spending, contractor payments, cost overruns, and per-beneficiary costs, with automatic variance alerts.

- Mid-term accountability mechanisms including statutory “mandate hearings” where ministries publish scorecards, citizens submit evidence, and televised scrutiny applies private sector performance logic to public service.

- Structured recall procedures triggered by constituencies when corruption, absenteeism, or severe non-performance breaches codified thresholds, with graduated responses from censure through funding freezes to by-elections.

- Investigative access rights enabling citizen-triggered audits for local projects above specified spending thresholds, resolved within statutory timeframes.

- Enforceable response obligations requiring time-bound, legally binding replies from elected representatives on registered queries, with non-compliance triggering penalties and public scoring.

- Comprehensive disclosure requirements mandating public mapping of familial political inheritance, beneficial business interests, and connections to taxpayer-funded contracts.

Converting Vote-Banks to Rights-Banks

Implementation demands specific, measurable steps. Annual “Use-of-Tax” statements should link major levies to recognisable public outcomes. Fiscal devolution and central scheme releases should be tied to disclosure compliance by states. Parliamentary sessions should feature mandatory hearings where ministries face citizen evidence on budget execution.

Every capital project above threshold spending should post costs, status, contractor details, overruns, and responsible officers on open ledgers. Accredited civil society organisations should be empowered to trigger targeted audits when complaint thresholds are met. Pilot recall referenda should begin at municipal levels before scaling upward.

These mechanisms exist in fragments worldwide—participatory budgeting in Latin American cities, recall provisions in parts of the United States, social audits in rural employment schemes, open contracting portals across Europe. India need not invent from scratch; it must integrate proven tools.

Democracy’s Debt to Its Investors

The Union raises trillions because citizens produce, earn, consume, invest, and save. When those revenues flow to government coffers, however, the citizen is escorted from the control room. It no longer suffices to claim that “you chose the government; that is your recourse.” Without enforceable rights to course-correct, interrogate, investigate, and receive binding answers, such recourse becomes rhetorical cover for fiscal extraction.

The Indian voter is not a supplicant seeking state largesse. The Indian voter is the principal capital provider to the Republic. A democracy that spends the people’s money owes something more substantial than gratitude every five years: transparency, accountability, mid-term power, and the right to demand answers.

Until that bargain is honoured, the many will continue financing the few whilst dignifying that arrangement with the name of freedom. True democratic governance requires not merely the right to vote, but the right to govern—continuously, transparently, and with enforceable consequence. Only then will India’s citizens cease to be hostages to their own democracy.